Current status of infrastructures of obstetrics and gynecology in South Korea

Article information

Department of obstetrics and gynecology is sort of disliked one every application period. The number of applicants failed to meet the quorum for 7 years. Application rate has not been improved though the quota was decreased. Decrease of birth rate can be a reason for decrease of demand for physicians of obstetrics and gynecology. However, for understanding this phenomenon, it is important to investigate the current status of human resources and facilities of obstetrics and gynecology and to compare medical costs for surgery of Korean obstetrics and gynecology with other surgical departments.

Between 2006 and 2012, the number of resident applicants, application rate for resident training and the number of doctors on duty of emergency care were investigated in 107 teaching hospitals in Korea. Supply of board-certified physicians in obstetrics and gynecology was also investigated between 2000 and 2013. The change in the numbers of clinics or hospitals capable of delivery between 2001 and 2008, income and expenditure on management of delivery room in 2006 and the medical costs for surgery and medical procedure of obstetrics and gynecology include vaginal delivery on December 2009 were searched. The comparison of the delivery costs between Korea and other countries was conducted.

A. Human resources of obstetrics and gynecology

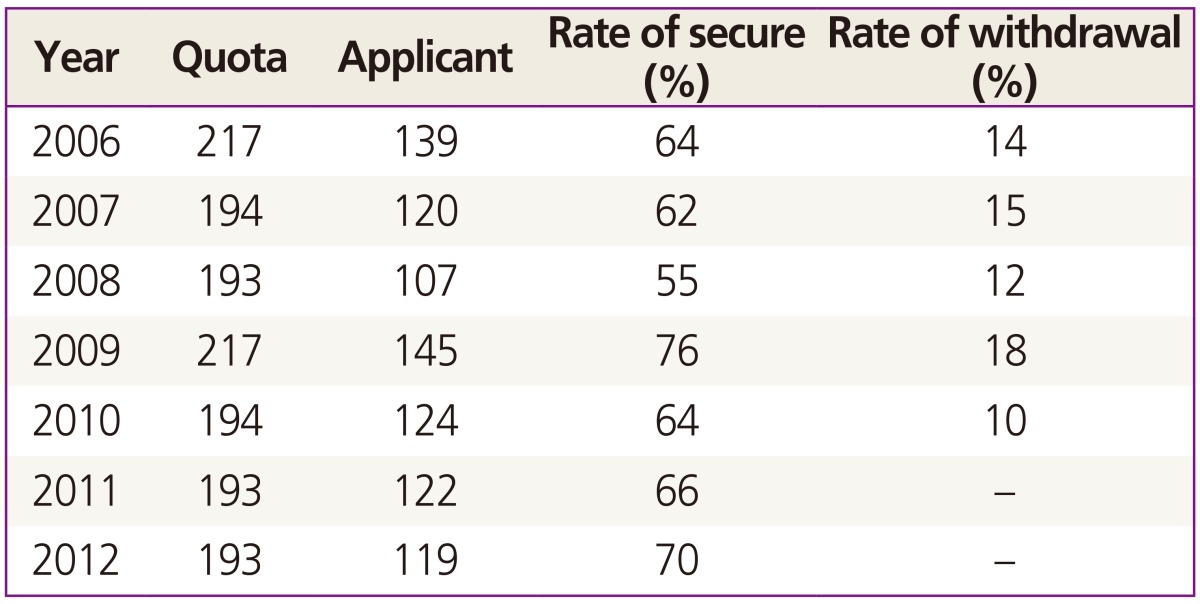

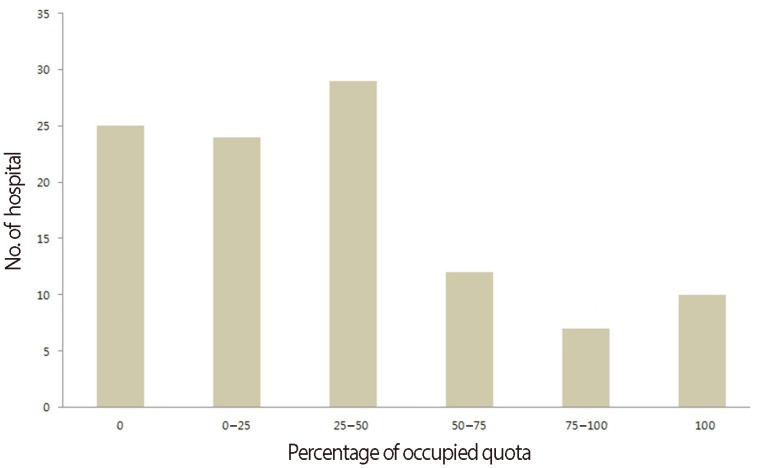

According to the data from Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 64% (median; range, 55% to 76%) of quota of resident trainee was acquired in department of obstetrics and gynecology. However, actual acquired percentage was 49% (median; range, 47% to 62%) considering dropout rate (Table 1). The 78 hospitals out of 107 hospitals could acquire less than 50% (Fig. 1).

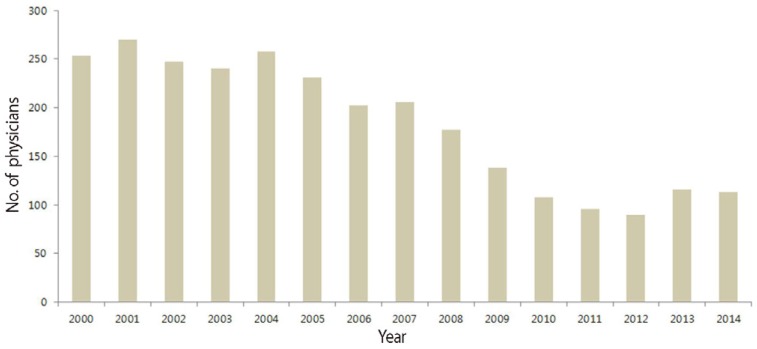

Decrease of application rate of obstetrics and gynecology resident training leads to decrease of board-certified physicians. The supply of the board-certified physicians of obstetrics and gynecology was decreased over the past decade. While more than 200 of board-certified physicians were supplied in early 2000s, less than half of those were supplied for the last five years (Fig. 2).

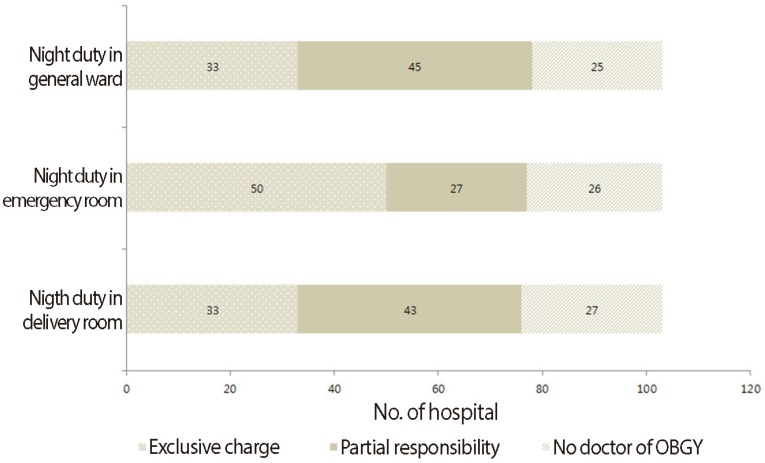

Decrease of resident trainee and board-certified physicians of obstetrics and gynecology means lack of physicians in practice. Resident trainee of obstetrics and gynecology had exclusive charge on general ward during the night in only 33 hospitals out of 107 hospitals in December 2009 and no physicians of obstetrics and gynecology was on call in 25 hospitals (Fig. 3). In addition, primary care in emergency of obstetrics and gynecology was possible by resident trainee or board-certified physicians of obstetrics and gynecology in only 50 hospitals out of 107 hospitals. On the other hand, nor resident trainee neither boardcertified physicians of obstetrics and gynecology participated in night duty of delivery room in 27 hospitals. Among those, no delivery was conducted during the night in 6 hospitals.

B. Changes in facilities of obstetrics and gynecology and medical costs

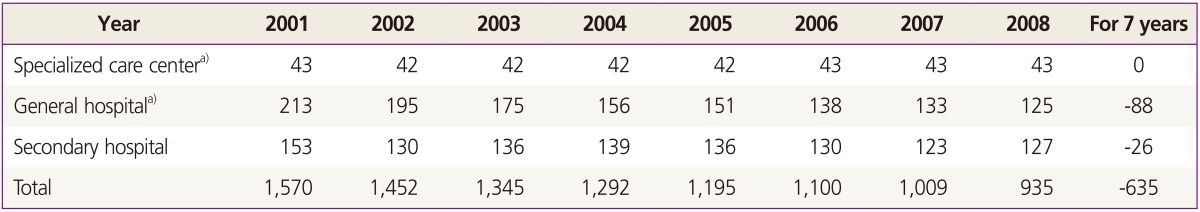

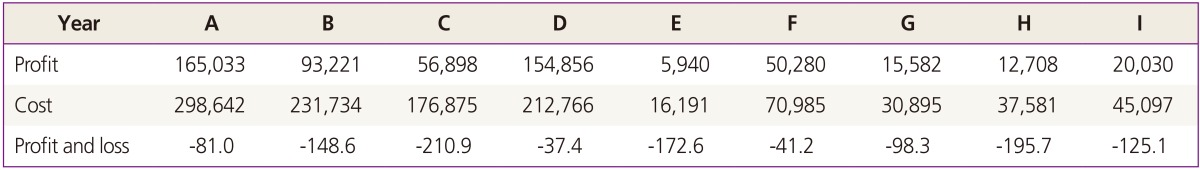

Vaginal delivery is the representative procedure in practice of obstetrics and gynecology. However, the number of clinics or hospitals capable of delivery was continuously decreased from 2001 to 2008 (Table 2), comparing to 2000 only 60% of clinics or hospitals remained in 2008. There were no changes in teaching hospital, which is mandatory to operate delivery room. Unlike teaching hospitals, closure of delivery room was continued in smaller then general hospital. It is hard to retain the practice and management of delivery room with current medical fee (Table 3). One hundred twenty-five percent (median; range, 37% to 210%) of loss was reported in 9 hospitals in the data of income and expenditure of management of delivery room in 2008.

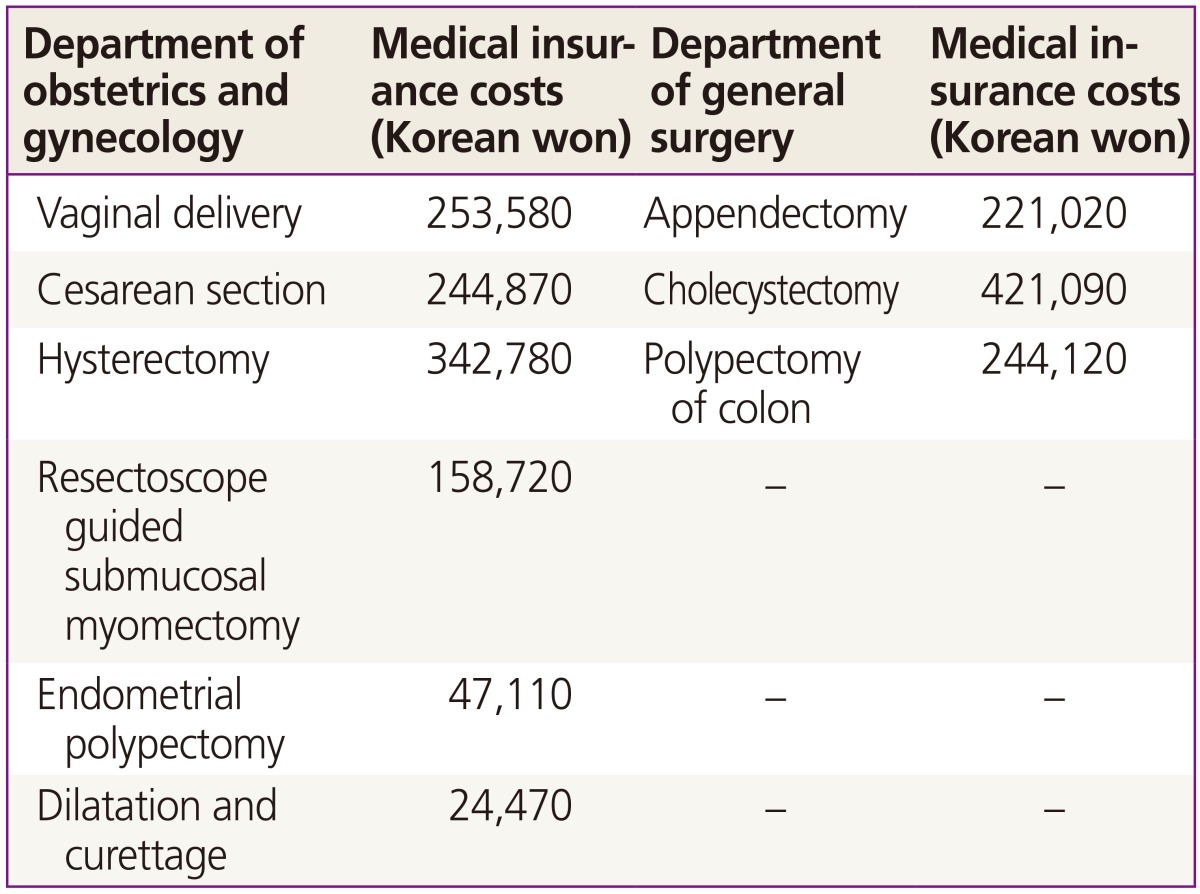

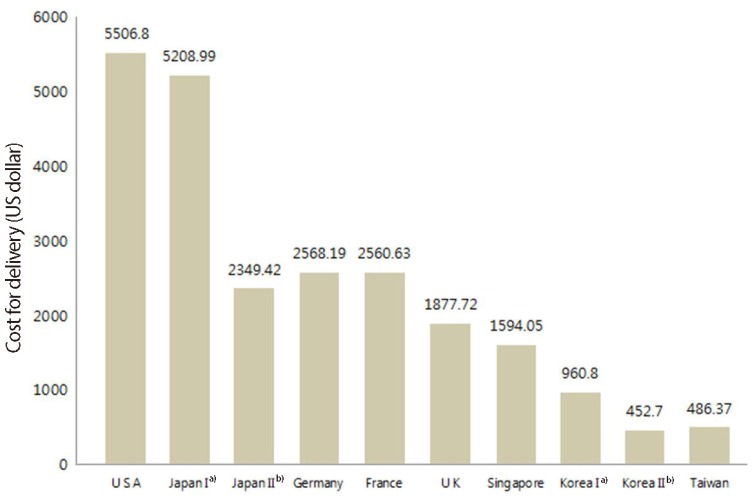

In terms of the input of manpower and time, the medical fee for procedures and surgery of obstetrics and gynecology was relatively lower than that of other surgery department in South Korea (Table 4). In addition medical costs for vaginal delivery of Korea were only 44% of that of average of other countries which were members of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (Fig. 4).

It was checked that only 50% of quota for resident training in department of obstetrics and gynecology remained and the supply of board-certified physicians in obstetrics and gynecology was continuously decreased. Emergency care for the patients of obstetrics and gynecology might not be performed due to manpower shortage and it is not difficult to estimate quality of primary care for the patients of obstetrics and gynecology would get worse and worse. Moreover clinics or hospitals capable of delivery are decreasing every year. On the other hand, the medical costs for vaginal delivery of Korea were remarkably lower than that of other countries. Human resources shortage and remarkably low medical costs lead to decrease of clinics or hospitals capable of delivery. Decrease of clinics influences on decrease of demand of physicians of obstetrics and gynecology. This is a vicious cycle. Therefore, it is not difficult to predict growing shortage of human resources and medical facilities of obstetrics and gynecology. To break the vicious cycle, realistic medical insurance system is necessary.

Acknowledgments

All the data in this article were provided from Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology.