Aortic dissection accompanied by preeclampsia in a postpartum young woman

Article information

Abstract

Aortic dissection is very rare in obstetrics, but it is a fatal disease. A 37-weeks primigravida woman with dyspnea and pitting edema presented to our emergency room. The patient was diagnosed with preeclampsia and underwent an emergency cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. The patient complained of severe dyspnea after the cesarean section, and the chest computed tomography scan was done. With the finding of aortic dissection, cardiopulmonary arrest occurred 5 hours after the cesarean section, and the patient died without reaction to cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. If a patient with preeclampsia complains of severe dyspnea or chest pain, aortic dissection needs to be suspected and a diagnosis should not be delayed.

Introduction

Aortic dissection is uncommon, but it is a life-threatening disease. Aortic dissection is difficult to distinguish from other heart or lung diseases, because it appears with a variety of symptoms. An accurate diagnosis is made only in 60% to 70% of hospitalized patients at an early stage [1].

Acute aortic dissection can occur with the connective tissues disorders, such as high blood pressure disorder during pregnancy, including preeclampsia, coarctation of aorta, and Marfan's syndrome [2]. Particularly, obstetricians have difficulties in making a diagnosis because aortic dissection in pregnancy happens very rarely. The majority of patients complain of typical chest pain [2], but this clinical symptom masks the underlying left ventricular dysfunction.

It has been reported in the literature review that deaths occurred by the rupturing of aortic dissection, which was suddenly outbroken after a cesarean section of the patients who were diagnosed with preelcampsia.

Case report

A 19-year-old primigravida woman at 37-weeks gestation with lower abdominal pain, dyspnea, and pitting edema presented to the emergency room at Dankook University Hospital. She had received a prenatal management at a local clinic, and there were no abnormal findings including the past medical history and family history. A headache or the right upper abdominal pain was not observed at her admission to the hospital.

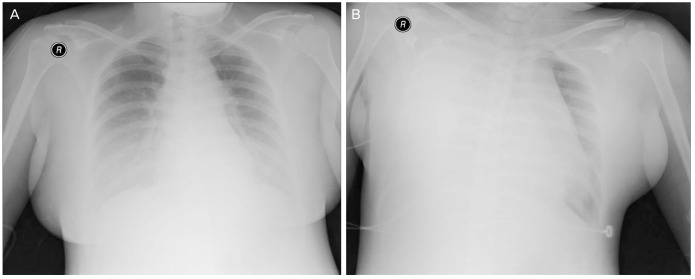

At the admission to the emergency room, laboratory findings were identified as follows: blood pressure of 160/90 mmHg, pulse rate of 79 beat/min, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, protein in urine (+++), hemoglobin concentration of 8.6 g/dL indicating anemia, platelet count of 181×103/µL, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine of 10.5/0/73 mg/dL, and aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase of 20/7 U/L. An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm, but a large amount of pleural effusion was observed on chest radiogram(Fig. 1A). Oxygen saturation was normal, and the estimated fetal weight and the amniotic fluid volume on ultrasound examination were also within the normal range.

(A) Preoperative anteroposterior chest X-ray showing increased opacity in both lower lung zone reveals bilateral pleural effusion. (B) Postoperative anteroposterior chest X-ray shows mediastinal widening with a large right pleural effusion.

The patient complained of labor pains at regular intervals of 5 minutes, and a fetal heart rate deceleration was shown on cardiotocogram. Her cervical dilation was 1 cm and effacement was 75% on a pelvic examination. She was diagnosed with preeclampsia and underwent an emergency cesarean section under the spinal anesthesia.

The baby was healthy with the weight of 2,900 g, and the Apgar score of 8 to 9 at 1 and 5 minutes; and there was no problem with the cesarean section. In 40 minutes after the surgery, the patient complained of severe dyspnea and chest pain with the blood pressure of 160/85 mmHg, pulse rate of 146 beat/min, respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation of 90%. On auscultation, the right lung sound was absent. Chest X-ray (Fig. 1B) and chest CT scan were done, and the chest tube was inserted.

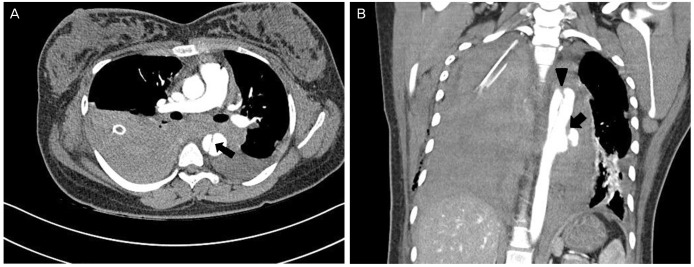

Aortic dissection with rupture was diagnosed with the finding of descending aortic dissection at the level of T3 to T7 and massive hemothorax on the chest computed tomography scan (Fig. 2) and it was classified DeBakey type III dissection. The patient was transferred to intensive care unit and was monitored. The patient did not receive intravenous antihypertensive medication because her blood pressure was maintained at 120/70 mmHg. However, cardiopulmonary arrest occurred 5 hours after the cesarean section, and the patient died without reaction to cardio-pulmonary resuscitation.

(A) An axial image of computed tomographic angiography of the thorax demonstrates a dissection of the descending thoracic aorta with the flap (arrow). (B) A coronal image of computed tomographic angiography of the thorax shows massive bilateral hemothorax and a ruptured dissection of the descending thoracic aorta (arrow head) between the T3 and T7 with saccular outpouching (arrow). It is classified Stanford type B or DeBakey type III dissection.

Discussion

Aortic dissection is a very rare disease, occurring at an estimated rate of 2.95/1,000,000 per year [3], and it is one of the most dreaded clinical conditions among aortic diseases. Hypertension is the main risk factor. Aortic dissection occurs 2 to 3 times more frequently in males than in females, and it is more common between the ages of 50 and 70 [4]. Other risk factors include Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, familial history of aortic dissection, pregnancy, aortic coarctation, Turner syndrome, trauma, etc. [5678]. Particularly, it has been stated that 50% of aortic dissections occurring in women of ages below 40 years is related to the pregnancy; but Oskoui and Lindsay [9] have disputed the result of previous report stated above.

Aortic dissection in pregnancy can occur in all stages of pregnancy, but it has been reported that the aortic dissection mostly occurred in the third trimester (51%) and in the postpartum period (20%), compared to the first trimester (6%) and the second trimester (10%) [5]. This case also occurred just after a cesarean section. Aortic dissection occurs at a higher rate in multigravida, with multigravida:primipara ratio of 3:2 [1011].

The possibility of aortic dissection should be considered in all pregnancy or postpartum women who complain of chest pain or back pain, and if they show any findings of widened mediastinum on the chest X-ray scan, high blood pressure with the symptoms, or having the previous pregnancy history in the past. Caution should be taken when a postpartum woman complains of vague pain, since the aortic dissection is hard to distinguish from the physiologic pain.

Historically, aortography was considered gold standard for the diagnosis of aortic dissection. More specifically, computed tomographic angiography, transesophageal echocardiography, and magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be both more accurate and less invasive for diagnosis of aortic dissection. But computed tomographic angiography have adverse effects from the injection of contrast agent and radiation into the fetus.

Classification schemes for aortic dissection are based on anatomic involvement of the aortic dissection. In the DeBakey classification, type I dissections originate in the ascending aorta and extend to at least the aortic arch; type II dissections involve the ascending aorta only; and type III dissections begin in the descending aorta, usually just distal to the left subclavian artery. In the Stanford classification, type A dissections involve the ascending aorta, and type B dissections are those that do not involve the ascending aorta. Type A dissections require emergency surgical repair, whereas medical therapy is usually the initial strategy for acute type B dissections. Surgical repair for Stanford type B is required in the following conditions: leakage or rupturing, severe compromise of an arterial trunk, continued or recurrent pain, extension of the dissection while the patient is receiving adequate medical treatment, or uncontrollable hypertension. Immediate management of aortic dissection includes stabilizing the patient with prompt attention to blood pressure reduction. Beta Blockers are the first drugs of choice because of their mechanism of lowering the rate of rise of ventricular force (dP/dt) and stress on the aorta. Intravenous agents are chosen for rapid onset. The treatments for aortic dissection in pregnancy are determined depending on the type of dissection, occurrence stage (in pregnancy, at delivery, or after delivery), and gestational age. For the anatomical classification of aortic dissection in pregnancy, the case of dissection involving the ascending aorta is 89%, DeBakey type I is 70%, and DeBakey type II is 19%. DeBakey type III is reported as 11% [5]. Cesarean delivery with aortic dissection in pregnancy should be primarily performed if the patient is hemodynamically stable. There are many different views regarding the appropriate time to perform the surgery for aortic dissection after cesarean section. This is because the use of anticoagulant is equired for the surgery; and if anticoagulant is used right after the delivery, uterine hemorrhage should be considered. Pumphyrey performed a surgery for the aortic dissection 48 hours after a cesarean section on the patient of 37 weeks gestation with DeBakey type II [12]. However, Snir et al. [13] reported that surgery for aortic dissection was performed immediately after the cesarean section. In addition, Zeebregts et al. [14] presented therapeutic guidelines based on types of aortic dissection as per Stanford classification. According to this, before 28 weeks' gestation, a surgery for aortic dissection is recommended to be performed while maintaining the pregnancy. After 32 weeks' gestation, primary cesarean delivery followed by the surgery is recommended. Between 28 and 32 weeks' gestation, the surgery is recommended to determine the fetal health status and maternal condition.

Not much is known about prognostic factors for aortic dissection in pregnancy, but risk of death is the greatest within the initial 2 weeks from the occurrence of aortic dissection. Fetal and maternal mortality with the aortic dissection is approximate 30%, and pre-hospital maternal mortality reaches at 30% [14]. Huang and others reported two cases of aortic dissection in association with preeclampsia. First case occurred during the postpartum period, and the second case occurred during the third trimester. However, both patients died due to delayed diagnosis, despite of the treatment [15]. In Korea, there were two case reports about aortic dissection associated with pregnancy. All cases were DeBakey type III aortic dissection which were successfully managed medically without surgical intervention, but the onset of aortic dissection was different, antepartum and postpartum respectively. The case we are reporting is different in that, the patient had preeclampsia, as to the two previous case reports had no underlying medical disease. To our knowledge, it is the first case of aortic dissection accompanied by preeclampsia. Although aortic dissection in pregnancy is very rare, it must be suspected in pregnant women who presents with abnormal chest pain, particularly associated with hypertension; and the diagnosis should not be delayed.

Notes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.