|

|

- Search

| Obstet Gynecol Sci > Volume 64(1); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

Regional lymph node (LN) dissection is a standard surgical procedure for endometrial cancer, but there is currently no clear consensus on its therapeutic significance. We aimed to determine the impact of regional LN dissection on the outcome of endometrial cancer.

Methods

Study subjects comprised 36,813 patients who were registered in the gynecological tumor registry of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, had undergone initial surgery for endometrial cancer between 2004 and 2011, and whose clinicopathological factors and prognosis were appropriate for our investigation. The following clinicopathological factors were obtained from the registry: age, surgical stage classification, Union for International Cancer Control tumor, node, metastasis classification, histological type, histological differentiation, presence or absence of LN dissection, and postoperative treatment. We retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathological factors and therapeutic outcomes for patients with endometrial cancer.

Results

Analysis of all subjects showed that the group that underwent LN dissection had a significantly better overall survival than the group that did not undergo dissection. Analysis based on stage showed similar results across groups, except for stage Ia. Analysis based on stage and histological type showed similar results across groups, except for stage Ia endometrial carcinoma G1 or Ia G2. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors indicated that LN dissection is an independent prognostic factor and that it has a greater impact on prognosis than adjuvant chemotherapy.

Many cases of endometrial cancer are detected at an early stage. Of all detected cases, 71.9% are diagnosed at stage I and 6.0% at stage II. Advanced cancers with extrauterine lesions are rare, with only 13.3% diagnosed at stage III and 7.5% at stage IV [1]. The standard treatments for endometrial cancer include total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingooophorectomy, and regional lymphadenectomy. In Japan, regional lymphadenectomy is performed in approximately 60-70% of patients with endometrial cancer [2]; of these, only a few cases have lymph node (LN) metastasis. Regional LN metastasis is one of the most important prognostic factors in endometrial cancer. If a LN is positive for metastasis, it is diagnosed as stage IIIc or higher, making the diagnostic significance of LN dissection abundantly clear. However, given that many cases show negative LN metastases, there is still a debate on the benefits of its therapeutic significance. Despite the existence of previous reports, the significance of regional LN dissection remains controversial, and there is no consensus within the medical community on its relevance.

The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) has a gynecological cancer registry (GCR) that records clinicopathological factors, treatment methods, and prognostic outcomes for several endometrial cancer cases in Japan [3]. Here, we analyzed the clinicopathological factors and treatment outcomes using data from the GCR of JSOG to examine the impact of regional LN dissection on endometrial cancer.

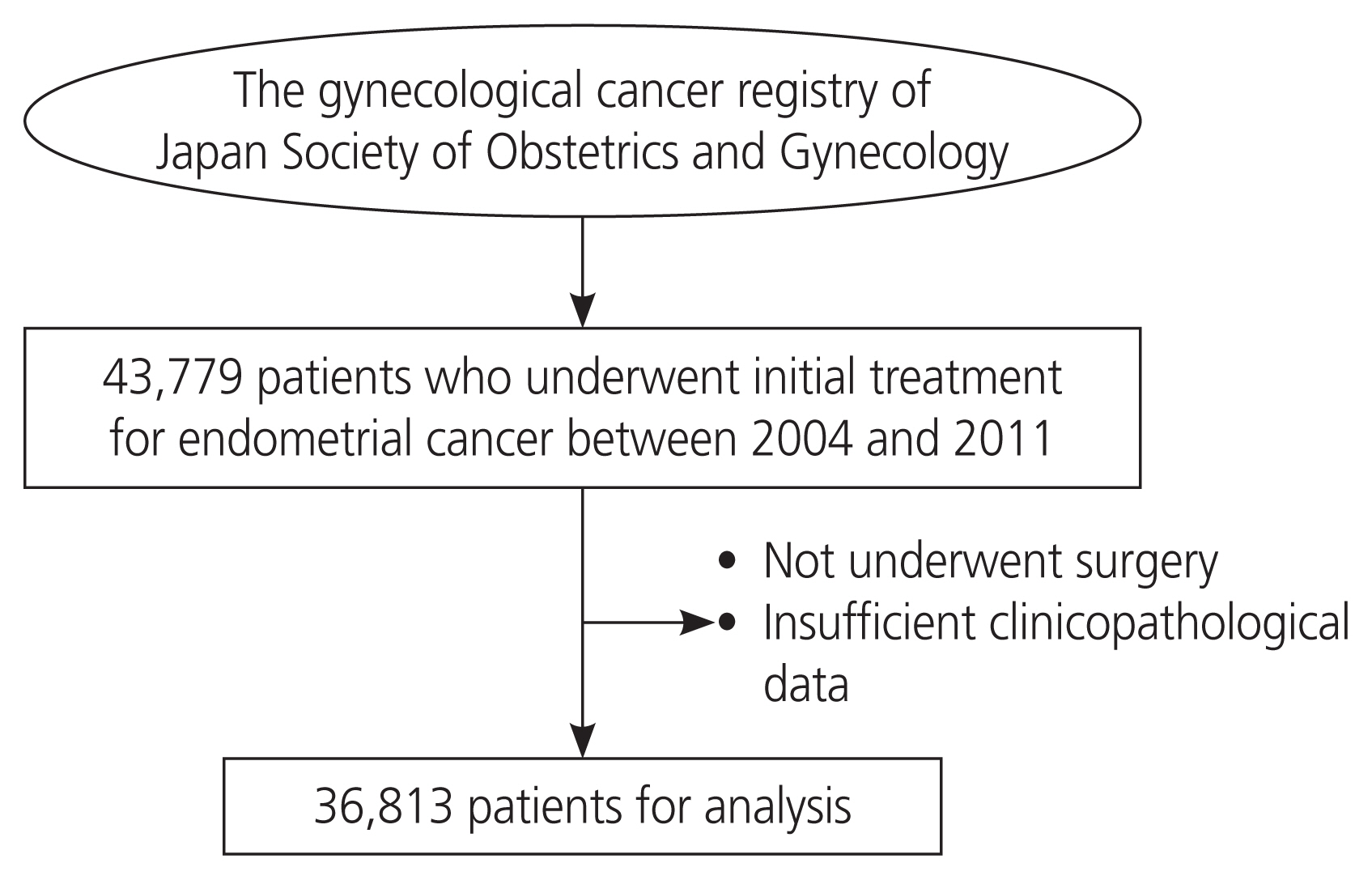

The subjects comprised 43,779 patients who were registered in the JSOG gynecological tumor registry and underwent initial surgery for endometrial cancer between 2004 and 2011. After receiving approval from the JSOG Ethics Committee, data on the clinicopathological factors and prognoses of these patients were collected. We excluded patients who had not undergone initial surgery, those with inappropriate registration of clinicopathological factors and prognostic outcomes, and those with a histological type of carcinosarcoma. Finally, a total of 36,813 patients were analyzed in this study (Fig. 1).

The clinicopathological factors that can be obtained from this registry include age, post-surgical stage classification (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] 1988), Union for International Cancer Control tumor, node, metastasis classification (version 7), histological type, histological differentiation, presence or absence of LN dissection, and adjuvant treatment. Prognostic information included whether the patient was alive and the last date of confirmed survival. The classification of recurrence risk used in this study has been described in the Japanese Treatment Guideline for Endometrial Cancer 2018 edition [4]. Information on the method of hysterectomy, extent of LN dissection, number of LNs dissected, presence or absence of lymph vascular space involvement, postoperative treatment regimen, number of cycles, and presence or absence of recurrence were not registered items and could not be analyzed. In this study, overall survival (OS) was defined as the period from the date of the initial surgery to the date of final prognosis confirmation or death from any cause.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The analysis of clinicopathological factors was performed using a χ2 test or Mann-Whitney test. In the univariate analysis of OS, a significant difference test was performed using the log-rank test and the Kaplan-Meier method. In addition, a multivariate analysis was performed with the available prognostic factors (age, surgical stage, histological type, histological differentiation, presence/absence of LN dissection, and presence/absence of postoperative therapy) using the Cox proportional hazards model. In each case, P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age of the subjects was 58 years (range, 14-97 years). Of the patients, 24,296 (66%) were classified as stage I, 3,313 (9%) as stage II, 7,362 (20%) as stage III, and 1,840 (5%) as stage IV. In terms of histological type, 18,406 (50%) patients had grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma, 8,098 (22%) had grade 2 endometrioid carcinoma, 3,681 (10%) had grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma, and 5,153 (14%) had non-endometrioid carcinoma. LN dissection was performed in 27,007 cases (73%) and was not performed in 9,806 cases (27%). Postoperative treatment consisted of adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) in 14,168 (38%) patients and adjuvant radiotherapy in 776 (2%) patients.

Table 2 shows the clinicopathological factors of LN dissected and non-dissected cases. For those who underwent dissection, the median age of the patients was 58 years (14-94 years) and for those who did not, the median age was 59 years (20-97 years); patients who underwent dissection were significantly younger (P<0.001). Among the dissected and non-dissected cases, 74% and 79% were of surgical stages I and II, respectively, and 26% and 21% were of stages III and IV, respectively. A significantly greater number of patients in the LN dissected group had advanced cancer (P<0.001). In terms of histological type and histological differentiation, 74% of the dissected cases and 75% of the non-dissected cases were of well-differentiated types (endometrioid carcinoma G1 or G2) and 26% of the dissected cases and 25% of the non-dissected cases were of the poorly differentiated types (endometrioid carcinoma G3 and non-endometrioid carcinoma). The poorly differentiated types were significantly more common in the LN dissected group (P=0.018). There was a low-risk of recurrence in 43% and 56%, an intermediate risk of recurrence in 16% and 12%, and a high-risk of recurrence in 41% and 33% of the dissected and non-dissected cases, respectively. Cases with an intermediate or a high-risk of recurrence were significantly more common in the dissected group (P<0.001).

From the analysis of all cases, the median observation period was found to be 1,610 days (0-2542 days). The 5-year OS rate was 90% in the LN dissected cases and 81% in the non-dissected cases. The 5-year OS rate was significantly higher in the LN dissected cases (P<0.001). Analysis by surgical stage revealed that the 5-year OS rate was 96% and 93% in stage I, 93% and 80% in stage II, 80% and 57% in stage III, and 39% and 22% in stage IV in the dissected and non-dissected groups, respectively. The 5-year OS rate was significantly better in the dissected group for all stages (stage I to stage IV; P<0.001, Fig. 2). In the classification, including the sub-classification, only the patients of surgical stage Ia had no significant difference in the 5-year OS rate (P=0.324).

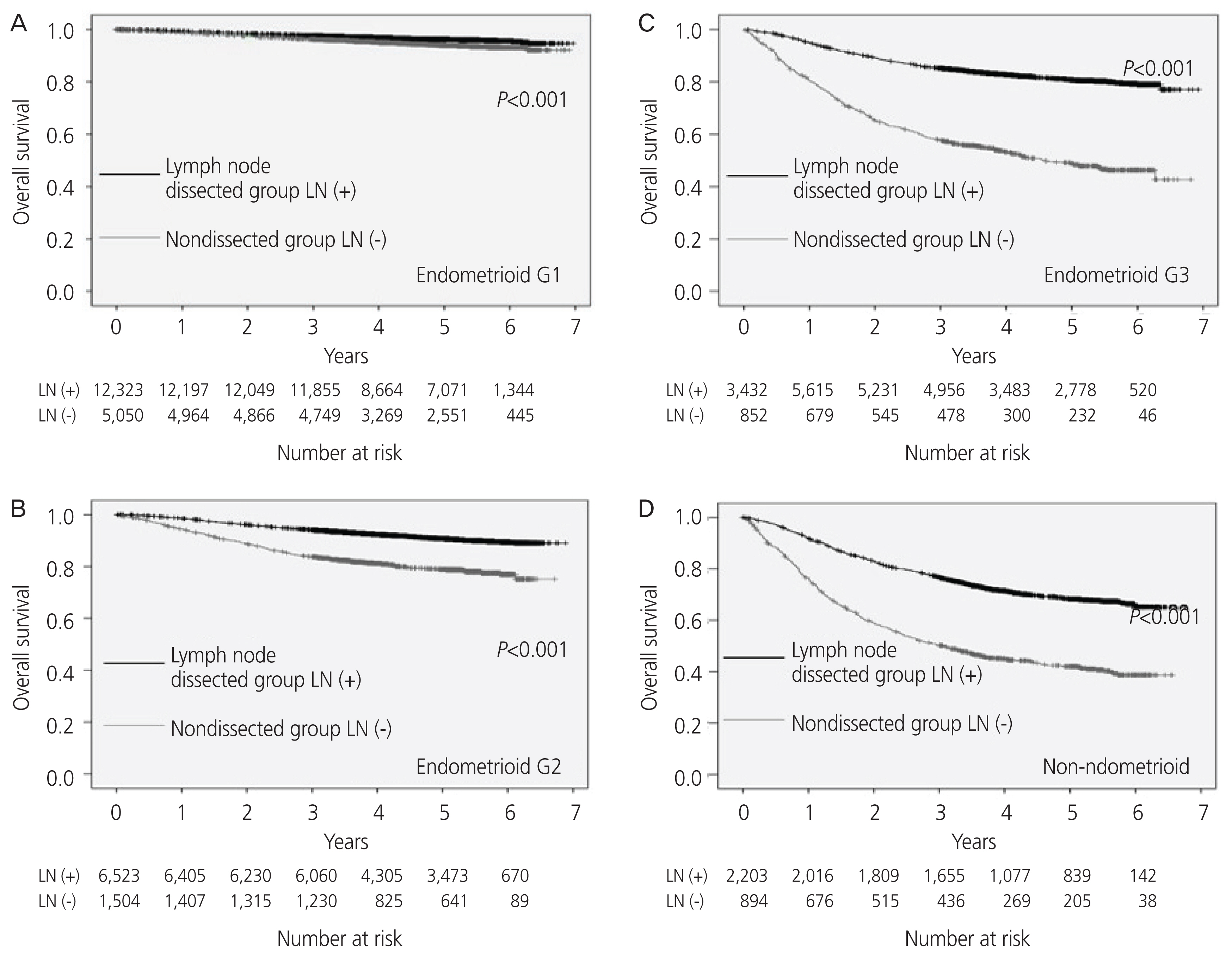

From the histological analysis, the 5-year OS rate was found to be 96% and 94% for G1, 91% and 79% for G2, 81% and 49% for G3, and 68% and 42% for non-endometrioid carcinoma in the dissected and non-dissected LN cases, respectively. The 5-year OS rate was significantly better for each histological type in the LN dissected cases (Fig. 3).

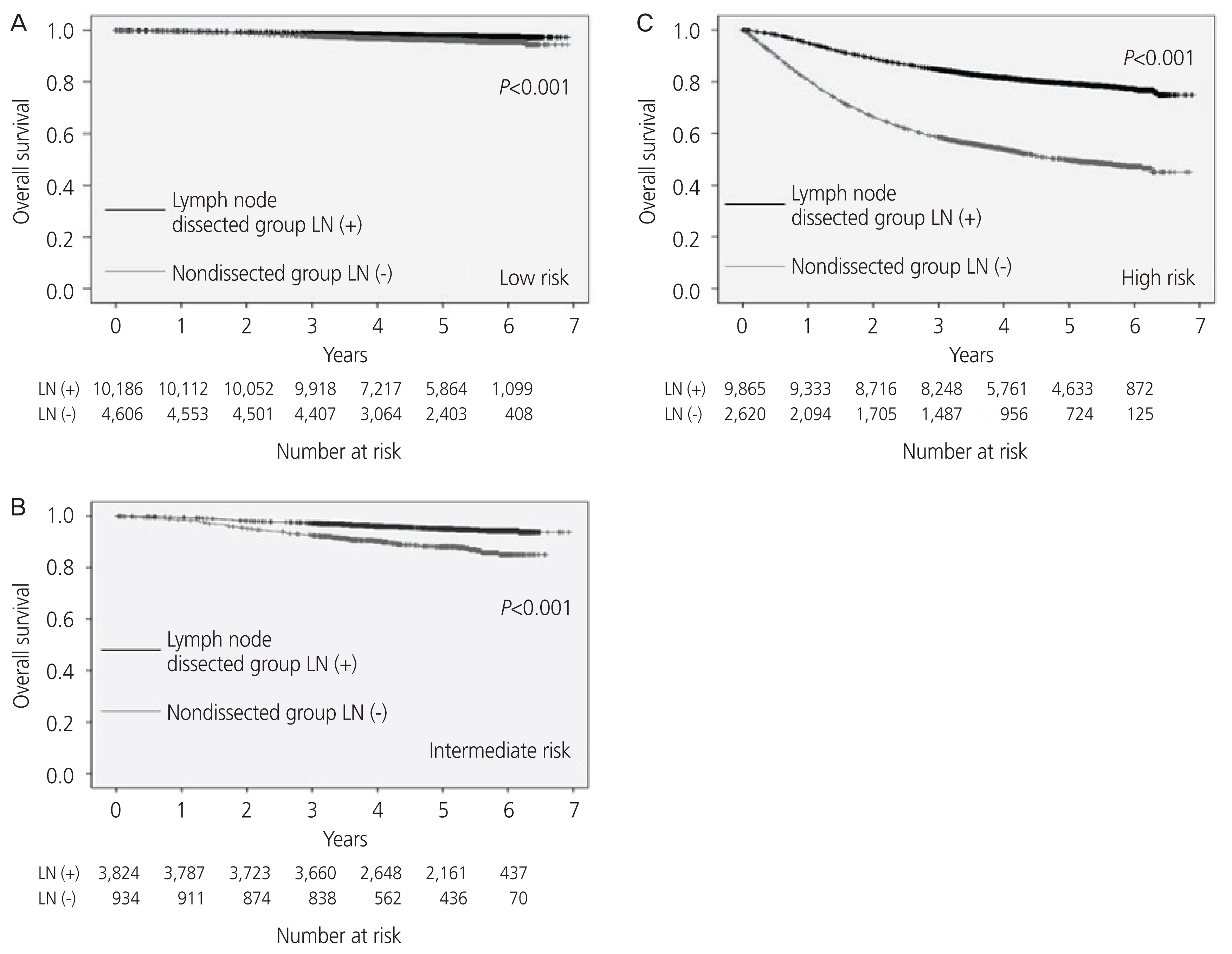

In the analysis by recurrence risk classification, the 5-year OS rate was 98% and 96% in the low-risk cases, 95% and 88% in the intermediate-risk cases, and 79% and 50% in the high-risk cases in the LN dissected and non-dissected cases, respectively. The 5-year OS was significantly better in the LN dissected cases for each risk group (P<0.001, Fig. 4). Further analysis of the group with a low-risk of recurrence revealed that there was no significant difference in the 5-year OS rate in stage Ia endometrioid carcinoma G1 or G2 (P=0.331, P=0.099).

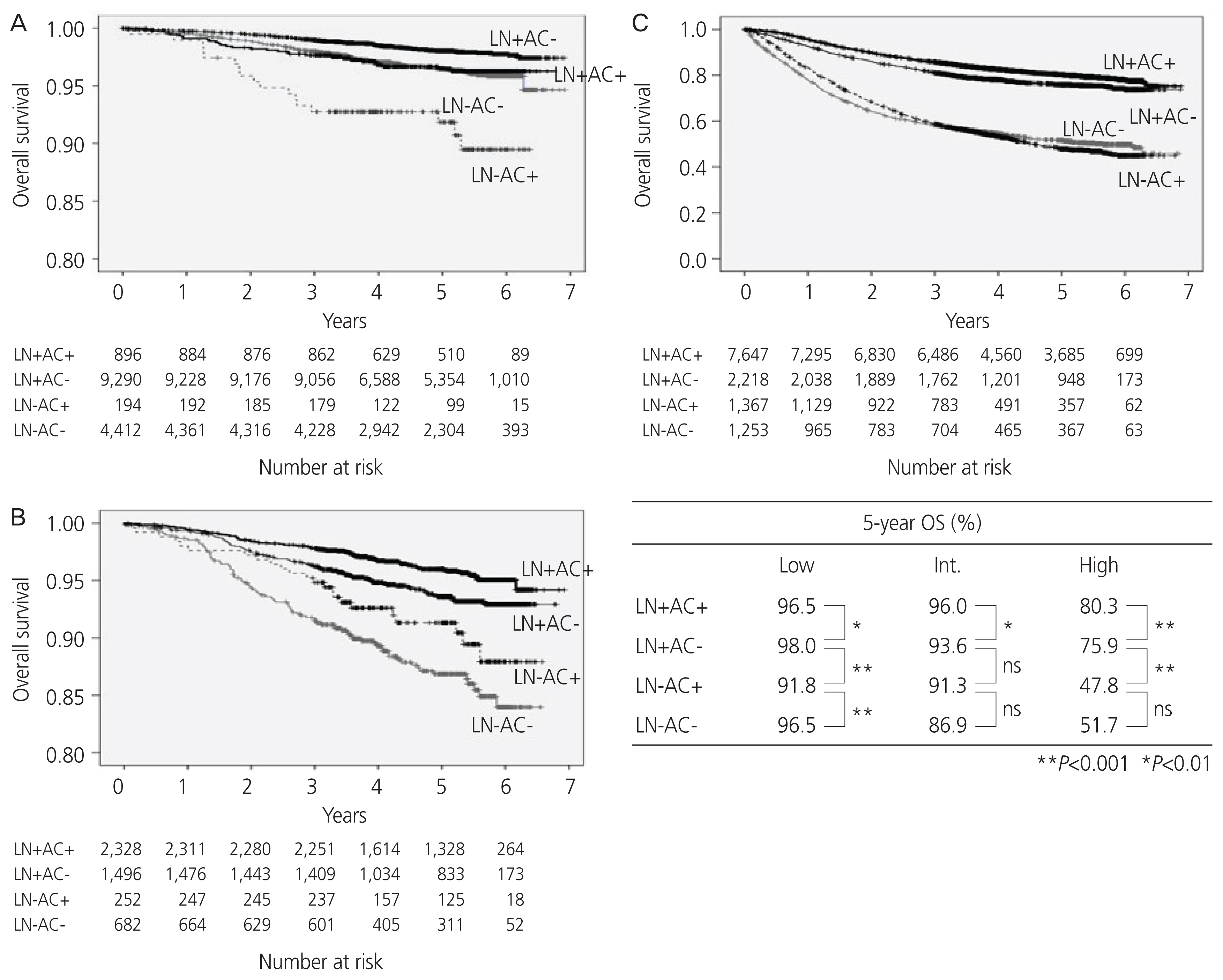

The patients in the low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups were further categorized into 4 groups based on the presence or absence of LN dissection (LN+/−) and the presence or absence of AC (AC+/−). The prognosis of each group was subsequently analyzed.

The 5-year OS rate of the low-risk group was 98.0% in the LN+AC−, 96.5% in the LN+AC+, 96.5% in the LN−AC−, and 91.8% in the LN− AC+ subgroups. The 5-year OS rate of the intermediate-risk group was 96.0% in the LN+AC+, 93.6% in the LN+AC−, 91.3% in the LN−AC+, and 86.9% in the LN−AC− subgroups. The 5-year OS rate of the high-risk group was 80.3% in the LN+AC+, 75.9% in the LN+AC−, 47.8% in the LN−AC−, and 51.7% in the LN−AC+ subgroups.

The LN+AC+ subgroup had significantly better prognosis in the intermediate-/high-risk groups; however, the LN−AC+ subgroup had a significantly worse prognosis than the LN+AC− subgroup, especially in the high-risk group. Therefore, the prognosis could not be improved by the administration of AC to patients who did not undergo LN dissection (Fig. 5).

A multivariate analysis of OS rate was performed using the prognostic factors of age, surgical stage, histological type, presence or absence of LN dissection, and presence or absence of AC; all of these data were obtained from the JSOG cancer registry. The results showed that all the above factors were also independent prognostic factors (Table 3). The hazard ratio (HR) for AC was 0.69 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-0.74; P<0.001), whereas the HR for LN dissection was 0.39 (95% CI, 0.36-0.41; P<0.001). The HR for LN dissection was much lower than that for AC.

In this retrospective study of a relatively large sample size, we analyzed the profiles of 34,575 patients. The distribution of surgical stage and histological type of the subjects was similar to that of the general population, based on the cancer registry data. Unlike most Western countries, the majority of the postoperative treatments of the subjects consisted of chemotherapy, rather than radiation therapy, which is one of the hallmarks of this study.

In this study, the group that underwent regional LN dissection had a better prognosis than the non-dissected group. When surgical staging was taken into consideration, the LN dissected group had a better prognosis than the non-dissected group in all surgical stages, except for stage Ia. Considering the surgical stage and histological type, the LN dissected group had a better prognosis than the non-dissected group at all surgical stages, except for stage Ia G1 and stage Ia G2. Therefore, regional LN dissection may improve the prognosis of endometrial cancers, except for patients at stages Ia G1 and Ia G2. The prognosis was significantly better in the LN dissected group without AC than in the non-dissected group with AC in high-risk cases. The multivariate analysis also showed that the HR for LN dissection was much lower than that for AC, suggesting that the impact of LN dissection on prognosis was greater than that of AC. Based on this finding, we do not recommend inadequate replacement of LN dissection with AC. There may be several reasons why the OS rate did not improve when chemotherapy was administered instead of lymphadenectomy. The possible reasons are as follows: 1) institutions that could not perform lymphadenectomy may have provided poor quality of surgery, and chemotherapy alone did not improve the prognosis sufficiently; 2) lymphadenectomy was not performed, making accurate staging impossible and resulting in possible underestimation of patients with stage IIIc or higher; and 3) there were patients with poor general condition who could not undergo lymphadenectomy owing to complications.

There are several studies on the therapeutic significance of regional LN dissection for endometrial cancer. Retrospective studies have reported that LN dissection significantly improved the prognosis of patients with stage I endometrioid carcinoma G3, invasion of more than half of the myometrium, or stage II endometrioid carcinoma [5,6]. The ASTEC trial, a prospective study that investigated the significance of pelvic lymphadenectomy (PLN), compared 686 patients with LN dissection and 683 who did not undergo dissection; the 5-year OS rate of the patients was 80% and 81%, respectively, with no significant difference between the 2 groups [7]. In this study, adjuvant radiotherapy was performed in fewer than 10% of the patients in the low-risk group and about half of the patients in the intermediate- and high-risk groups. Another prospective Italian study compared 264 LN dissection groups and 250 non-dissection groups; the researchers found a 5-year OS rate of 85.9% and 90.0%, respectively, with no significant between-group differences [8]. However, these trials included a large number of low-risk patients with LN metastasis, and the median number of dissected LNs in the ASTEC trial, which was 12, might have been too small. Furthermore, the SEPAL study, a retrospective cohort study conducted in Japan, compared 325 patients who underwent PLN alone with 346 patients who underwent PLN along with para-aortic lymphadenectomy (PAN). There was no significant difference in the recurrence-free survival (RFS) or OS rate in the low-risk group. However, in the intermediate- and high-risk groups, the 5-year RFS rate was 64.8% and 80.7%, and the 5-year OS rate was 72.6% and 83.2%, in the groups that underwent PLN alone and PLN+PAN, respectively. The RFS and OS rates were, therefore, significantly better in the PLN+PAN group than in the PLN alone group [9]. Multivariate analysis revealed LN dissection to be an independent prognostic factor, with an effect on improving prognosis only when patients with a high-risk of LN metastasis were assessed.

The results of our study support the findings of the SEPAL study. Because chemotherapy is used in most cases in Japan as an adjuvant treatment [1,2,10], the results may differ from those reported in Europe and the United States, where adjuvant radiation therapy is administered [11,12]. The control of pelvic lesions by adjuvant radiation therapy was replaced by regional LN dissection, and further control of systemic lesions by chemotherapy may lead to a prolonged prognosis [13].

The strengths of this study are that it included a large number of cases and that most institutions in Japan were included in the registry of all the cases, thereby reducing the bias among institutions or cases. Conversely, the limitations are that this study is retrospective, the data required for detailed analysis were insufficient, the prognostic data included only OS, and the following biases could not be excluded. The first bias is that the non-dissected group was likely to include cases with poor prognosis for other reasons. Potential high-risk patients, such as those with severe complications and the elderly, tended to undergo no systematic lymphad-enectomy, which may have contributed to the shortened OS in the non-dissected groups. Although patients in the non-dissected group were significantly older, the median age was almost the same (58 and 59 years old in the dissected and non-dissected groups, respectively), and a difference with a significant impact on OS was unlikely.

The second bias could be latent LN metastases in the non-dissected group. LN metastases may be missed in stage I to stage IIIb patients who have not undergone systematic LN dissection. Such false-negative cases may contribute to the shortened OS in the non-dissected group. However, in Japan, many patients undergo magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography before surgery, and it is unlikely that the apparent LN metastasis was overlooked during imaging. The third bias is that the enrollment data lack qualitative assurance of the procedure of hysterectomy and LN dissection. Because the details of hysterectomy and definition of LN dissection have not been determined, LN biopsy may have been registered as LN dissection, and the effects of such discrepancies on OS cannot be denied. However, these factors might reduce any improvements in the prognosis of LN dissection cases, and a strict registration of surgical procedures can lead to further differences.

In consideration of the above points, this study suggests that LN dissection may have a prognostic effect on endometrial cancer. The elimination of as much bias as possible is essential for an accurate evaluation of therapeutic outcomes, and a phase 3 randomized clinical trial is deemed necessary.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) for access to data from the gynecological cancer registry (GCR). We are grateful to Dr. Yasunori Sato for helpful discussions on statistical analysis and Ms. Keiko Yoshizawa for her secretary help.

Notes

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) Ethics Committee (No.67).

Fig. 1

The subjects of this study, as recorded in the gynecological cancer registry of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; TNM, tumor, node, metastasis; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Fig. 2

The overall survival rate analyzed by the stage (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] 1988); (A) stage I, (B) stage II, (C) stage III, (D) stage IV. LN, lymph node.

Fig. 3

The overall survival rate analyzed by the histological type; (A) endometrioid carcinoma G1, (B) endometrioid carcinoma G2, (C) endometrioid carcinoma G3, (D) non-endometrioid carcinoma. LN, lymph node.

Fig. 4

The overall survival rate analyzed by the recurrence risk classification; (A) low-risk cases, (B) intermediate-risk cases, (C) high-risk cases. LN, lymph node.

Fig. 5

The overall survival (OS) rate analyzed by the treatment and recurrence risk; (A) low-risk group, (B) intermediate-risk group, (C) high-risk group. LN, lymph node; AC, adjuvant chemotherapy; ns, not significant.

Table 1

Patients’ characteristics

Table 2

Clinicopathological factors of patients with and without lymphadenectomy

Table 3

Multivariate analysis of clinicopathological factors

References

1. Yamagami W, Nagase S, Takahashi F, Ino K, Hachisuga T, Aoki D, et al. Clinical statistics of gynecologic cancers in Japan. J Gynecol Oncol 2017;28:e32.

2. Shigeta S, Nagase S, Mikami M, Ikeda M, Shida M, Sakaguchi I, et al. Assessing the effect of guideline introduction on clinical practice and outcome in patients with endometrial cancer in Japan: a project of the Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) guideline evaluation committee. J Gynecol Oncol 2017;28:e76.

3. Nagase S, Ohta T, Takahashi F, Enomoto T. 2017 Committee on Gynecologic Oncology of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Annual report of the committee on gynecologic oncology, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology: annual patients report for 2015 and annual treatment report for 2010. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2019;45:289-98.

4. Yamagami W, Mikami M, Nagase S, Tabata T, Kobayashi Y, Kaneuchi M, et al. Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology 2018 guidelines for treatment of uterine body neoplasms. J Gynecol Oncol 2020;31:e18.

5. Trimble EL, Kosary C, Park RC. Lymph node sampling and survival in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1998;71:340-3.

6. Chan JK, Cheung MK, Huh WK, Osann K, Husain A, Teng NN, et al. Therapeutic role of lymph node resection in endometrioid corpus cancer: a study of 12,333 patients. Cancer 2006;107:1823-30.

7. Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. ASTEC study group. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymph-adenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet 2009;373:125-36.

8. Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, Alberto Lissoni A, Signorelli M, Scambia G, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1707-16.

9. Todo Y, Kato H, Kaneuchi M, Watari H, Takeda M, Sakuragi N. Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1165-72.

10. Watanabe Y, Kitagawa R, Aoki D, Takeuchi S, Sagae S, Sakuragi N, et al. Practice pattern for postoperative management of endometrial cancer in Japan: a survey of the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2009;115:456-9.

11. Ko EM, Funk MJ, Clark LH, Brewster WR. Did GOG99 and PORTEC1 change clinical practice in the United States? Gynecol Oncol 2013;129:12-7.