Maternal age-specific rates of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in Korean pregnant women of advanced maternal age

Article information

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association of maternal age with occurrence of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in Korean pregnant women of advanced maternal age (AMA).

Methods

A retrospective review of the amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling (CVS) database at Gangnam and Bundang CHA Medical Centers, between January 2001 and February 2012, was conducted. This study analyzed the incidence of fetal chromosomal abnormalities according to maternal age and the correlation between maternal age and fetal chromosomal abnormalities in Korean pregnant women ≥35 years of age. In addition, we compared the prevalence of fetal chromosomal abnormalities between women of AMA only and the others as the indication for amniocentesis or CVS.

Results

A total of 15,381 pregnant women were selected for this study. The incidence of aneuploidies increased exponentially with maternal age (P<0.0001). In particular, the risk of trisomy 21 (standard error [SE], 0.0378; odds ratio, 1.177; P<0.001) and trisomy 18 (SE, 0.0583; odds ratio, 1.182; P=0.0040) showed significant correlation with maternal age. Comparison between women of AMA only and the others as the indication for amniocentesis or CVS showed a significantly lower rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities only in the AMA group, compared with the others (P<0.0001).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that AMA is no longer used as a threshold for determination of who is offered prenatal diagnosis, but is a common risk factor for fetal chromosomal abnormalities.

Introduction

Pregnancy in advanced age is defined as childbirth at the age of 35 years or order regardless of whether the childbirth is the first or not. Recently, the percentages of pregnancies in advanced age have shown a gradual increase as women have entered the workforce in increasing numbers. In South Korea, the percentages of pregnancies in women of advanced age have more than doubled, increasing from 6.2% in 1999 to 15.4% in 2009 [1].

Fetal chromosomal abnormalities may be caused by a nondisjunction phenomenon that occurs in the period of meiosis during maternal oogenesis, which has been reported to have a direct association with maternal age. Therefore, pregnancy in advanced age is a critical risk factor for fetal chromosomal abnormalities [2-4].

Currently, fetal chromosomal abnormalities due to maternal age have been reported to include trisomy 21, trisomy 18, trisomy 13, triple X syndrome, and Klinefelter's syndrome [5].

As the percentages of pregnancies in women of advanced age have increased, there has been increasing demand for prenatal genetic counseling that helps to predict the risk of fetal chromosomal abnormalities depending on age. Most of the data were obtained from studies of women in North America or Europe. However, rare data from study of fetal chromosomal abnormalities depending on age targeting Korean women have been reported [6].

Against this background, the intention of this study was to examine the incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities depending on maternal age and to investigate correlation between fetal chromosomal abnormalities and maternal age, which targeted Korean pregnant women who underwent amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling (CVS). In addition, this study examined if there was any meaningful difference in the incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities between cases where only advanced age of pregnant women was considered as an indication for amniocentesis or CVS and cases where other indications were considered for such examinations.

Materials and methods

This study targeted 15,454 pregnant women who underwent amniocentesis or CVS in Gangnam and Bundang CHA Medical Centers during the period from January 2001 to February 2012 and was approved by Institutional Review Board in CHA Medical Center. This study was conducted as a retrospective study based on genetic information and inpatient and outpatient charts. However, 71 persons whose age could not be determined and 2 persons whose indication for amniocentesis or CVS could not be confirmed were excluded from this study. As a result, the cases of 15,381 pregnant women were included. Age of the cases was the age at the time of delivery.

Fetal chromosomal abnormalities were classified according to numeric and structural chromosomal abnormalities. The numeric chromosomal abnormalities were divided again according to autosomal and sex chromosomal abnormalities. In regard to structural chromosomal abnormalities, normal variations such as heterochromatin, satellite chromosomes and pericentric inversion of chromosome 9 were excluded from the abnormal category.

For analysis of maternal age-specific rates of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in pregnant women of advanced maternal age (AMA), maternal age beyond 35 years was segmented with a one-year interval. In addition to, among women ≥35 years of age, when only AMA was considered as indication of amniocentesis or CVS was performed, analysis was also performed to determine whether there was any difference in incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities compared to cases where other indications were considered. Logistic regression analysis was performed in order to investigate correlation between increase in maternal age and fetal chromosomal abnormalities. In addition, SPSS ver. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis of the study results. Significance probability of less than 0.05 was considered to show statistical significance.

Results

Among pregnant women who underwent amniocentesis or CVS during the study period 15,381 persons were selected for inclusion in this study. Age of the cases ranged from 19 years to 52 years. Average age was 34.0 years (±4.3); age distribution of the entire group of study subjects is shown in Fig. 1.

According to the results of fetal chromosomal examination, 14,818 cases (96.34%) were found to have normal fetus chromosomes while 563 cases (3.66%) were found to have abnormal fetus chromosomes. Among the abnormal cases (3.66%), 357 cases (2.32%) had numeric chromosomal abnormalities, while 206 cases (1.34%) had structural chromosomal abnormalities. With respect to numeric chromosomal abnormalities, trisomy 21 was found in 181 cases (1.18%), which was the highest frequency. Then, trisomy 18 was found in 72 cases (0.47%), Turner's syndrome in 41 cases (0.27%), Klinefelter's syndrome in 28 cases (0.18%), trisomy 13 and triple X syndrome in 14 cases for each (0.09%), and XYY syndrome in 7 cases (0.05%), in this order.

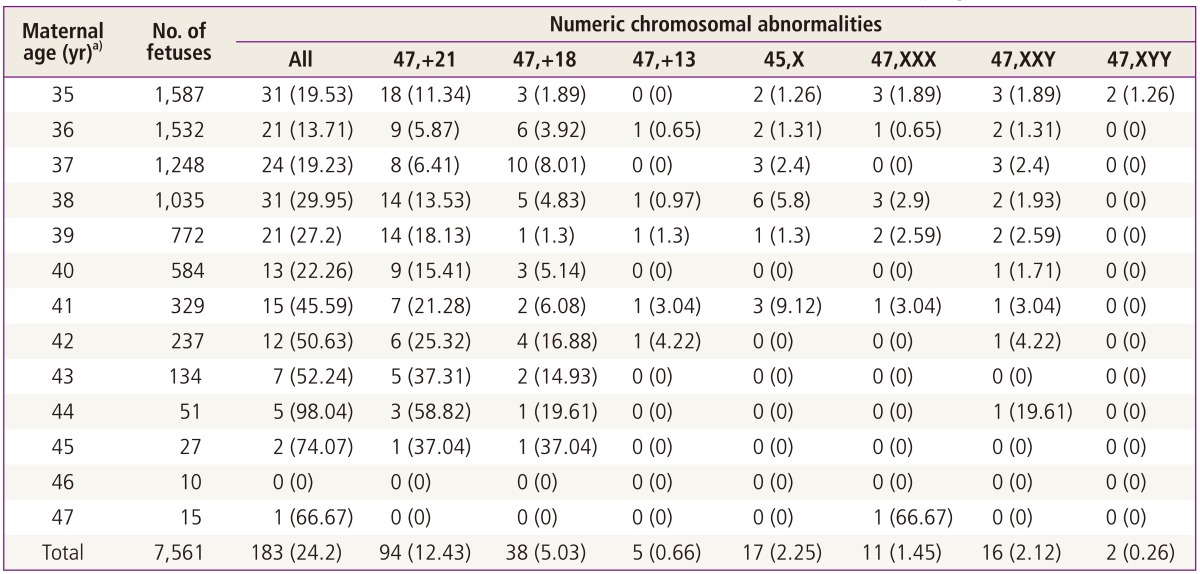

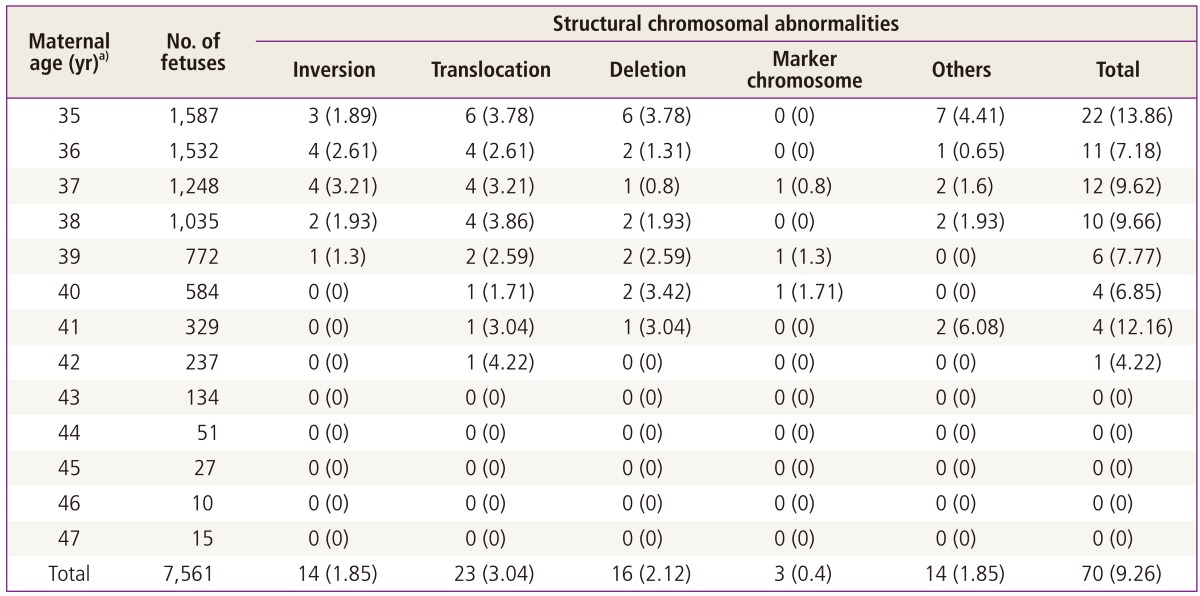

Tables 1, 2 show the analyses of the incidence rate of numeric and structural chromosomal abnormalities when age was increased by a one-year interval among women older than 35 years at the time of delivery. Trisomy 21 showed an incidence rate of 11.34 out of 1,000 cases at the age of 35 years, 15.41 cases at the age of 40, and 37.04 cases at the age of 45. Trisomy 18 showed an incidence rate of 1.89 out of 1,000 cases at the age of 35 years, 5.14 cases at the age of 40, and 37.04 cases at the age of 45, which is a sharp increase.

Incidences of structural chromosomal abnormalities found in amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling

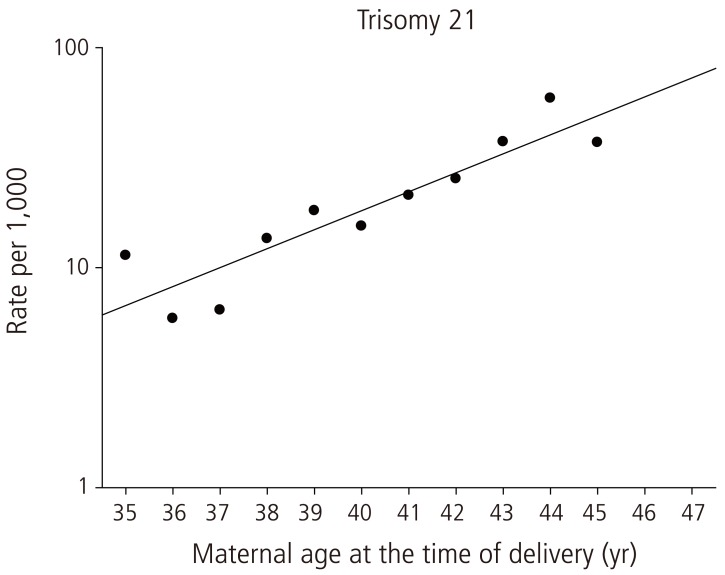

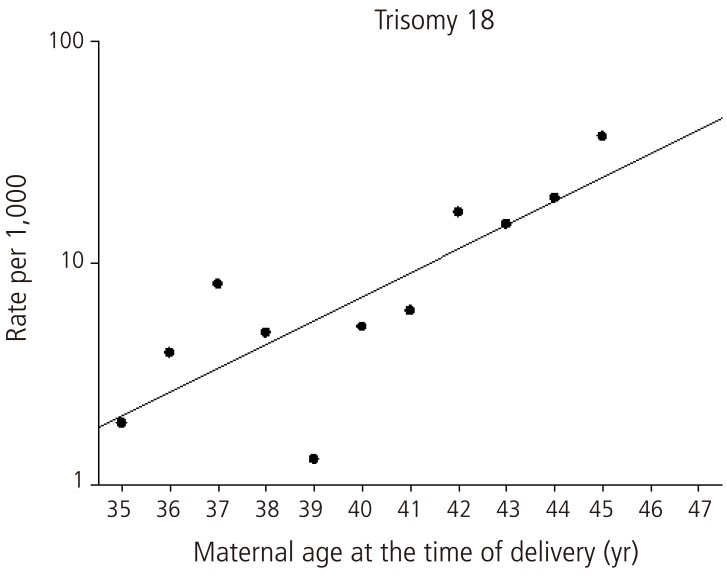

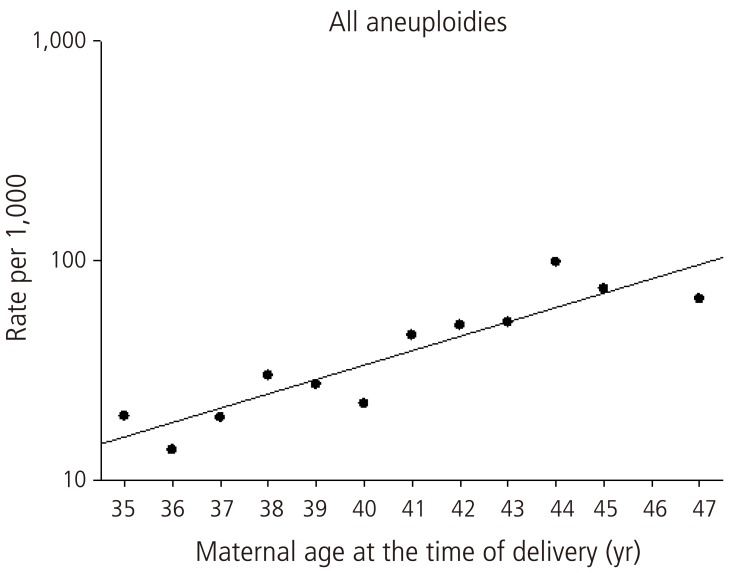

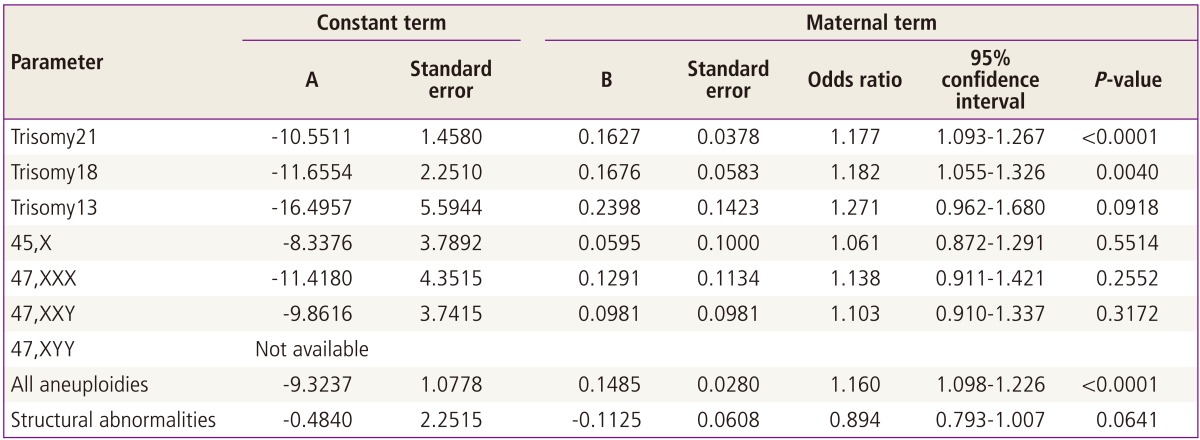

According to the results of logistic regression analysis, trisomy 21 and trisomy 18 showed close correlation with age. In other words, as age increased by one year, odds ratio of trisomy 21 tended to increase by 1.177 times (Table 3, Fig. 2). According to increase in age by one year, odds ratio of trisomy 18 also tended to increase by 1.182 times (Table 3, Fig. 3). In addition, in regard to all of the fetal aneuploidies, odds ratio also tended to increase by 1.160 times as age increased by one year (Table 3, Fig. 4).

Parameters and standard errors of logistic regression equations for fetal chromosomal abnormalities diagnosed at amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling

According to the results of this study, trisomy 13, Turner's syndrome, triple X syndrome, Klinefelter's syndrome, and structural chromosomal abnormalities did not show any significant correlation with maternal age (Table 3). XYY syndrome was found in two of the study subjects. Therefore, due to the very small number, analysis of the correlation between fetal chromosomal abnormalities and age was not possible.

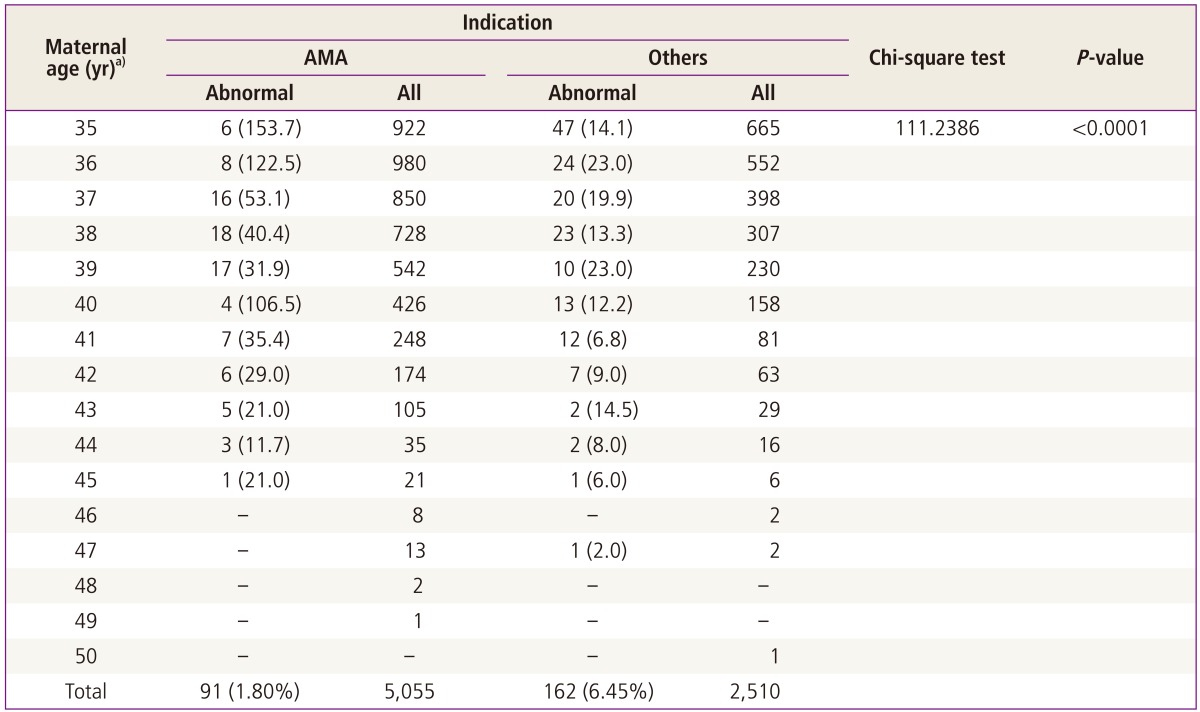

When only advanced age of women aged 35 years or older was considered as indication of amniocentesis or CVS were performed, the incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities was 1.80%. When other indications, including AMA were considered, the incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities was 6.45%. As a result, incidence of fetal chromosomal abnormalities was found to be significantly low when only advanced age was considered as an indication. However, both the AMA only group and other indication groups showed an increasing tendency in the expected rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities with the increase in age (Table 4).

Discussion

This study targeted pregnant women who underwent amniocentesis or CVS in South Korea in order to analyze correlation between fetal chromosomal abnormalities and maternal age. As the percentages of pregnancies in advanced age have increased in Korea, demand for prediction of risk of fetal chromosomal abnormalities depending on age in prenatal genetic counseling has also increased. However, data from studies targeting Korean women have rarely been reported. Consequently, this study has significant meaning in that it targeted Korean women and it utilized a large quantity of data that had accumulated over the past 10 years. Because fetal chromosomal abnormalities were examined among women in high-risk groups who underwent amniocentesis or CVS, incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities was relatively higher than incidence rate in the normal group.

A number of studies have reported that fetal chromosomal abnormalities showing a close association with maternal age included trisomy 21, trisomy 18, trisomy 13, triple X syndrome, and XYY syndrome. In 2010, Park et al. [6] published a research paper on a study of fetal chromosomal abnormalities depending on maternal age among Korean women. In a study targeting 2,032 women who underwent amniocentesis due to the sole indication of AMA, they analyzed correlation between fetal chromosomal abnormalities and maternal age. They reported that risk of trisomy 21, trisomy 18, triple X syndrome, and all aneuploidies showed a significant increase according to increase in maternal age. In this study, risk of trisomy 21, trisomy 18, and all of the fetal aneuploidies was found to show a significant increase according to increase in maternal age. In other words, as maternal age increased by one year, odds ratio of trisomy 21 tended to increase by 1.177 times, odds ratio of trisomy 18 tended to increase by 1.182 times, and odds ratio of all of the fetal aneuploidies tended to increase by 1.160 times. In addition, a sharp increase was found in incidence rate per 1,000 cases of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18 at the age of 45. However, because the number of cases at the age of 46 or older was very small, analysis of correlation between fetal chromosomal abnormalities and extreme maternal age was not possible. No significant correlation with maternal age was found in trisomy 13, Turner's syndrome, triple X syndrome, XYY syndrome, and structural chromosomal abnormalities. In particular, according to the statistics, trisomy 13, Turner's syndrome, and triple X syndrome were not found to show any significant correlation with maternal age. However, there was limitation in that the number of study subjects with each type of abnormality was too small to determine whether the resulting value was significant.

Amniocentesis is usually performed after 16 weeks, while CVS is generally performed within 10 to 12 weeks. If spontaneous abortion occurs before 12 weeks, more than 50% of cases are likely to be attributable to fetal chromosomal abnormalities. According to the results of studies on analysis of abnormal karyotype frequency depending on gestational age, the frequency was higher as the gestational age was lower [7]. In this study, a separate adjustment was not made for cases where fetal chromosomal abnormalities caused spontaneous abortion before amniocentesis or CVS was performed. Therefore, it is considered that there may be a slight difference from the actual incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities.

In addition, this study compared incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities between when only pregnancy in advanced age was considered as an indication for performance of amniocentesis or CVS and when other indications as well as AMA were considered among women older than 35 years. The results of comparison demonstrated that the incidence rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities was significantly high when other indications, including pregnancy in advanced age were considered for performance of genetic testing. Recently, remarkable development has been achieved not only in ultrasonography but also various prenatal screening tests. According to Malone et al. [8] in 2005, when prenatal screening test was performed using the combined method (i.e., sequential or integrated test) in a medical institution where experienced medical staff worked, detection rate of fetal chromosomal abnormalities was reported to be 90% or higher. Therefore, these results support the opinion that advanced age of a pregnant woman cannot be considered as a sole indication for amniocentesis, as shown in a Practice Bulletin published by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology [9]. However, genetic testing has been recommended for pregnant woman aged 35 years or older worldwide for the past 35 years. Despite the recently published guidelines, quite a few obstetricians still consider the age of 35 years as a cutoff for genetic testing [10]. According to recent studies conducted in Colorado of the US, birth rate of children with Down's syndrome increased when frequency of amniocentesis was reduced among women aged 35 years or older [11,12]. Consequently, maternal age is a factor that cannot be completely excluded from examination of fetal chromosomal abnormalities. In particular, advanced age of 35 years or older can be used as indication for conduct of prenatal genetic testing for pregnant women who did not undergo a separate screening test previously or could not provide exact information. Currently, thanks to development of not only a serum screening test but also precision ultrasound, the possibility of detection of fetal chromosomal abnormalities before childbirth has increased. Therefore, for more precise analysis of fetal chromosomal abnormalities, prenatal genetic counseling along with serum screening test, ultrasound screening, past history of fetal chromosomal abnormalities, or obstetrical history of pregnant women, rather than a simple reference to maternal age is needed.

It is believed that the results of this study can be used as basic data that are suitable for domestic circumstances when prenatal genetic counseling is provided for investigation of risk of fetal chromosomal abnormalities depending on maternal age. In addition, conduct of future study of association with fetal chromosomal abnormalities targeting Koreans and persons with a broader range of age will be needed.